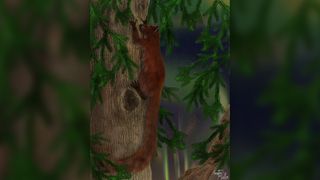

52 million years ago, strange primates lived in complete darkness in the Arctic

During the Eocene, the Arctic was a warm, swampy place that these primates called home.

About 52 million years ago, when the Arctic was warm and swampy but still shrouded in six months of darkness during the polar winter, two small primates scampered around, using their strong jaw muscles to chew the tough vegetation that managed to survive at the gloomy northern pole, a new study finds.

The two newfound primates — which belong to the already established primate genus Ignacius, and were given the new species names of I. dawsonae and I. mckennai — were small, weighing in at an estimated 5 pounds each (2 kilograms). They are the earliest known example of primates living in the Arctic, according to a new study published Wednesday (Jan. 25) in the journal PLOS One.

This finding is based on an analysis of fossilized jaws and teeth found on Ellesmere Island in Northern Canada. North of Baffin Bay, the island lies just south of the Arctic Ocean. It is about as far north as you can get in Canada.

"If you think about their modern relatives, either primates or flying lemurs, these are among the most tropically adapted, warm-weather loving of all mammals, so they would be the about the last mammals you would expect to see up there, north of the Arctic Circle," study senior author Christopher Beard, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Kansas, told Live Science.

The two species lived during the Eocene epoch (56 million to 33.9 million years ago), a period of intense planetary warming. At the time, there were no ice caps at the poles, and Ellesmere Island would have had a warm and muggy climate akin to that of today's Savannah, Georgia, according to study first author Kristen Miller, a doctoral student in Beard's lab at the University of Kansas.

Related: Why haven't all primates evolved into humans?

In fact, temperatures on Ellesmere Island were hospitable enough to host a diverse ecosystem of unlikely animals, including early tapir-like ungulates and even crocodiles, snakes and salamanders, according to earlier paleontological discoveries.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While Eocene arctic dwellers did not have to deal with extreme temperatures, life in the warm Arctic wasn't without its challenges. Due to the tilt of the Earth's axis, the sun doesn't rise on the island for half of the year. "We've got six months of winter darkness and six months of summer daylight," Miller said.

The main challenge for animals living so far north is a lack of food. Under such conditions, vegetation is likely to be scarce during the long, dark winters, so the researchers hypothesize that Arctic animals in the Ignaceous genus likely subsisted on tough-to-chew foods, such as seeds or tree bark. To make meals out of such difficult foods, the researchers found that, compared with the Arctic primates' more southerly relatives, their cheekbones protrude farther out from their skulls, which means that their jaw muscles likely did as well.

"The mechanical result of moving these masticatory muscles forward is you generate greater bite forces," Beard said.

Adaptations to northern latitudes don't stop with the jaw. The animals were much larger than their southerly relatives, too. "Five pounds doesn't sound very big, but compared to the ancestors of these guys, it's a giant," Beard said. "The close relatives with these animals that we find in Wyoming are the size of chipmunks."

Their relatively large size is expected. Overall, there is a general trend in ecology called Bergmann's rule that states that the farther animals live from the equator, the larger they tend to be. Size is a common adaptation to cooler temperatures, and yes, for a type of animal typically found in the tropics, the climate of modern-day coastal Georgia would be quite cool, necessitating a large size to minimize heat loss.

The Eocene's warming allowed many species to shift their ranges northward, a trend that ecologists are now seeing among modern species due to human-caused climate change. As the planet warms, more species will likely colonize the Arctic, but as in the case of Ignacius, many won't simply colonize, but may diversify into new species once there.

"Given a little bit of time, species are going to evolve their own distinctive features that will enable them to adapt even better to the Arctic," Beard said. "I think it's a real dynamic picture of what's going to happen in the Arctic in the future with anthropogenic warming.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.